By Sanjoy Sanyal

Foreign entrepreneurs corner the lion’s share of investment coming into Africa. It has been whispered in industry conferences, ranted about in social media posts and written about in research reports. And now, Larry Madowo, the US-based Kenyan journalist has written about this in mainstream media: Silicon Valley has deep pockets for African startups – if you are not African.

For the last two years, me and my colleagues – Chen Chen and Molly Caldwell- from the World Resources Institute have been examining why international impact investors have poured in millions of dollars into a handful of clean energy companies but ignored local entrepreneurs.

- FIRST REASON: Foreign investors are not based in Africa, so they do not meet local entrepreneurs.

As we were beginning the project, a colleague from one of our sponsoring organizations – DOEN Foundation and Wallace Global Fund – suggested that I speak to an impact fund manager of a European family office. She had already invested in energy access companies operating in Africa. She gave me time for a short call and was frank: “We are told that there are no local entrepreneurs. The employees working in the companies we invest in are learning the skills of what it takes to run businesses.” We met another European investor who told us that her firm had met several local entrepreneurs but “for us based in Europe it is really hard to do the due diligence”.

But investors like them are in the minority. We interviewed 20 investors who had made investments in clean energy companies. Thirteen had offices in Nairobi. If seven did not make investments in local entrepreneurs because they just did not meet them, what about the other 13?

- SECOND REASON: Foreign investors have no interest in looking out for local entrepreneurs

Some foreign investors do have offices and staff in Nairobi. However, the partners and the investment committee members are all foreigners. They would rather invest in companies run by foreign entrepreneurs. After all it is easier to understand and trust people who are like oneself. This reason sounds very plausible. But we also met enough investment funds run by local fund managers. We met the Kenyan manager of an early stage fund set up by donors with the specific purpose of supporting climate friendly enterprises. He agreed that it has been hard to invest in energy companies. We met the team which manages a debt fund specifically targeted at small and medium enterprises. Several other investment fund managers are run by Kenyans of South Asian origins. This enterprising community runs many of the businesses that dot the lovely Parklands and Westlands localities of Nairobi.

We tried to understand if they have not looked at investment proposals from Kenyan business owners. An experienced investment manager of Kenyan-origin told me: “Look, we have been here for a long time, we have looked at over 200 companies, but we have not met any local entrepreneurs.” The reasons varied. We were told: “The local entrepreneurs are not interested in setting up these businesses. They would rather set up traditional businesses – real estate, retail, hotels.” “They do not have the ability to make good quality presentations and robust financial models.”

- THIRD REASON: There are no investable local clean energy entrepreneurs

Perhaps that was the answer? Local entrepreneurs were not building clean energy businesses. Even if they were, they were too small and very risky. The World Bank, with support from UKAID and the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, had set up the world’s first Climate Innovation Centre in Nairobi in 2012. Could it have been a failed effort and had not produced any entrepreneurs? It would not have been the first time a development initiative had failed.

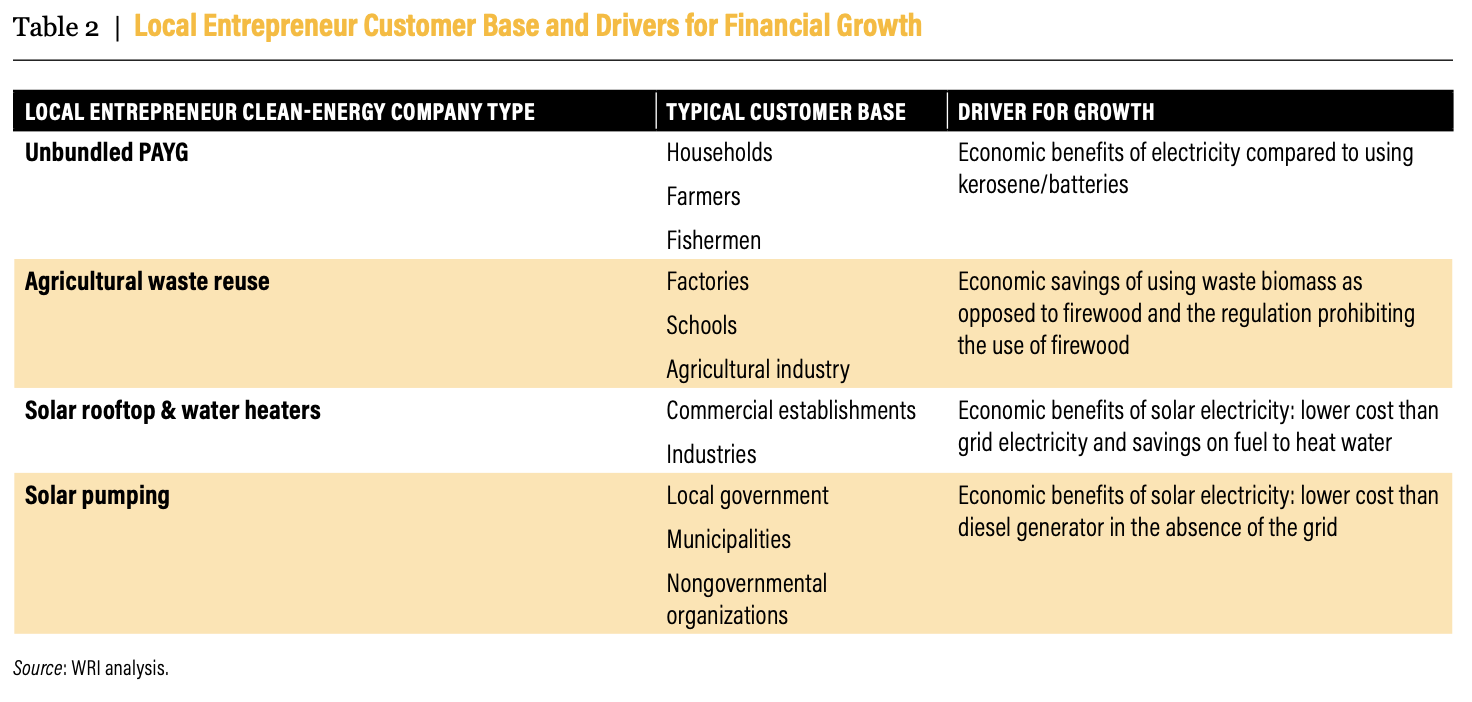

Unfortunately, that too was not true. In visit after visit, I met entrepreneurs who were running businesses with annual revenues between $500k to $2 million with positive EBILD (Earnings Before Interest, Lease, and Depreciation). I met entrepreneurs like Ameet Shah, who hails from Mombasa and studied in the University of Cambridge, running a solar rooftop business. I met Rajesh Haria, who had inherited a family business in beads, and is now a large distributor of solar lights. Taher Zavery runs a cotton ginning factory set up by his grandfather and has expanded into biodiesel which they produce from crushing cotton seeds. Jane Wangari started a business from her backyard, while nursing her six month baby. She is now supplying biomass briquettes to large factories. I met entrepreneurs like Gathu Kirubi, a doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley, David Wanjau and Teddy Odindo, who are distributing everything from solar home systems, solar pumps, solar fishing lights to rural communities on a “pay-as-you-go basis.”

- THE SOLUTION: It is really a straightforward issue of tailoring investment products

I stumbled on the solution as I started describing the businesses to investors.

Family businesses with an history of two generations were not investable as we want to invest in risky early stage business with lots of growth potential.” It did not matter that these family-run businesses had experience in managing the complex and changing business environment.

Solar rooftop companies and biomass briquette companies which provide clean energy solutions to large organizations are not investable as “we are looking to invest in companies that create impact at the bottom of the pyramid.” No matter that the only way to move a society out of poverty is to create jobs.

The companies distributing PAYG products are not investable because “we would like to invest in companies that can scale across Africa.” It did not matter that these local distribution companies were the ones providing customer credit and needed capital to do so.

Looking at it from this standpoint, the problem looks more like an opportunity to invest small amounts of capital in companies growing modestly. Not all companies will develop path breaking technologies and scale across the continent. Many companies will be take these new technologies and implement them at customer sites. Many others will be ensuring that consumers can get and use the products they need. Most of them will not have exponential growth but as long as they can earn money at a profit they provide an investment opportunity. Local currency debt – as me and my colleagues have argued in our paper – could be an appropriate investment for companies that have stable cash flows. In Kenya, even smaller companies are often forced to borrow in foreign currency which exposes them to fluctuation risks and hedging costs. It prohibits local entrepreneurs who do not have export earnings from growing. A variation of a debt instrument is where a loan is paid with a share of the company’s revenue. A seed fund – which invests small amounts of equity capital in early stage companies- could be yet another. All these options allow for companies to get some external capital, grow a bit and then come back for more. It is also a way for investment managers to manage risks.

Investors exploring these opportunities can seek inspiration from other emerging economies. Caspian, an Indian impact investor, provides debt from $150k (in local currency) to a range of companies creating social and environment business. Its clients include solar home system and cookstove companies selling products in rural areas. It has also invested in solar rooftop companies and biomass briquettes which serve larger industries. In Mexico, the New Ventures group has set up Viwala, a digital loan platform where borrowers pay a royalty on their revenue. An example of a seed fund is Blume Ventures in India. Its founder, Kartik Reddy, jokes that when “he started he and his partner ran around cutting $150k checks” He now manages a larger fund and has re-invested in some of the companies from his initial days.

There is an unserved market of local Kenyan entrepreneurs and to address them, investors must seek inspiration from others and try new investment opportunities that include smaller seed investments and a variety of debt and loan models.

+++++++++++

About the Author

Sanjoy Sanyal is the founder of Regain Paradise, which enables investments in environmental businesses. He was a Senior Associate with WRI when the Impact Investors Blind Spot: Local Clean Energy Entrepreneurs in Kenya was written. He is also an Advisor in Caspian Debt, whose structure has been suggested as a possible solution in this article.